One of the great unknowns for today’s senior is the cost of healthcare. Fidelity estimates that a recently retired senior couple will spend nearly $300,000 on out-of-pocket healthcare expenses — not including the costs of long-term care. That’s an alarming exclusion, given that long-term care is among the priciest and most commonly needed forms of senior healthcare. Statistically speaking, seven of 10 people will require some level of long-term care in their lifetime.

The takeaway is clear. As you and your loved ones age, it’s imperative to plan for the costs of senior care.

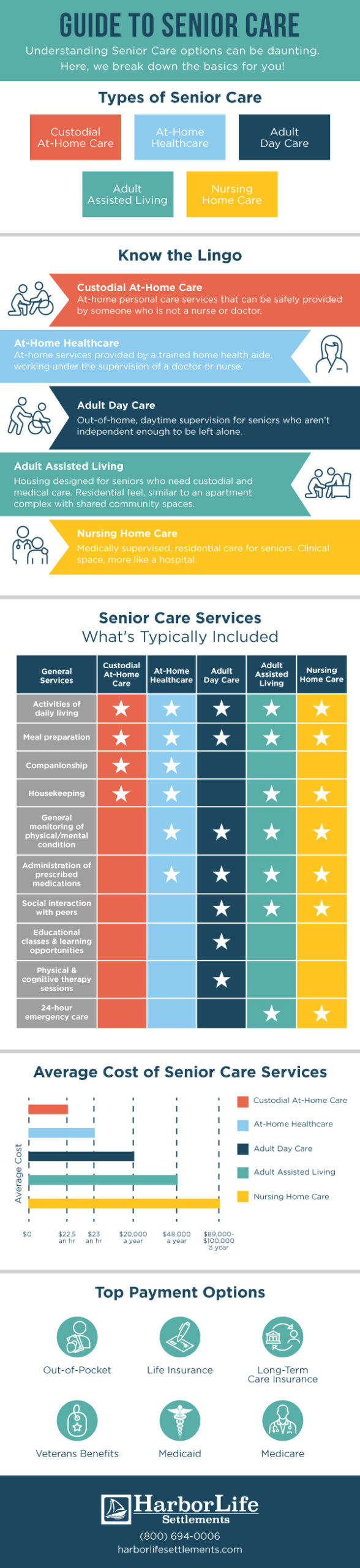

The average costs of senior care

Senior care costs vary widely. Full-time adult day care, one of the most affordable forms of senior care, costs about $1,625 monthly. A full-time, in-home health care worker would charge more than double that amount, or about $4,400 a month. And residential care in a nursing home ranges from $8,200 to $9,500 monthly.

Those are today’s average costs, but they’re likely to rise significantly in the coming years. Assuming a moderate 3% inflation rate, the cost of a full-time, in-home health aide would reach nearly $5,900 monthly in just 10 years. Under the same assumption, the monthly cost of a private room in a nursing home will eclipse $11,000 by 2029.

Ways to pay for senior care

Most households don’t have $5,000 or $10,000 in excess monthly income, so family members have to get creative to fund senior care costs. Here are six options to consider, individually or in combination with one another.

- Out-of-pocket. Many families cover their senior care costs with their own assets. Savings accounts, investment accounts, and home equity are straightforward sources of cash. Unfortunately, paying out-of-pocket for long-term healthcare services puts the senior at risk of insolvency in the future. That creates other problems, but there is one positive. Once the senior’s assets are wiped out, he or she would likely qualify for Medicaid, which will cover the most expensive forms of senior care.

- Life insurance. Life insurance can be converted into cash in several ways. The senior could borrow against a life insurance policy’s cash value, surrender a cash-value policy back to the insurer, or sell the policy outright in a life settlement (or viatical settlement if the senior is terminally or chronically ill). Some policies may additionally allow for terminally ill insureds to cash out part of the policy in what’s called an accelerated death benefit. Of those options, life settlements and accelerated death benefits typically generate the most cash.

- Long-term care insurance. Long-term care insurance reimburses the insured for in-home and out-of-home medical care under certain conditions. A medical doctor must certify that the senior needs help with activities of daily living (ADLs) such as eating, toileting, and grooming. Once the senior is deemed eligible for benefits, reimbursements are subject to daily and lifetime caps as defined in the policy. Also, the insurance must be initiated while the senior is still healthy. Even then, premiums for long-term care insurance are high enough to be unaffordable for many households.

- Veterans benefits. The VA’s Aid and Assistance benefit provides up to $2,170 monthly to cover the cost of nursing homes, assisted living, adult day services, and in-home care. To be eligible, the senior must already qualify for the basic VA pension and require assistance with ADLs.

- Medicaid. Medicaid coverage is an option for impoverished seniors. For those who meet very strict income and asset requirements, the state-run insurer will pay for long-term care costs and, in some cases, the costs of adult day care.

- Medicare. Medicare may pay for short-term stays in a skilled nursing home or intermittent/part-time home health services. Medicare does not help with the costs of custodial care, assisted living, long-term nursing home stays, or Alzheimer’s or dementia care.

Types of senior care services

The most common types of senior care services are custodial, at-home care; at-home healthcare; adult day care; adult assisted living; and nursing home care. Here’s an overview of each, including average costs.

1. Custodial at-home care

What is custodial, at-home care?

Custodial care, also called nonmedical care, is a set of personal care services that can be safely provided by someone who is not a nurse or doctor. Trained home care aides provide these services, which typically include:

- Help with grooming, dressing, and toileting

- Companionship

- Housekeeping

- Meal preparation

- Transportation to medical and other appointments

- Assistance with the senior’s exercise regimen

You and your home care aide together would review any physician recommendations and design the exact services and care plan.

How much does a non-medical caregiver cost?

Nationwide, nonmedical caregivers charge $22.50 hourly on average. The rate, however, varies significantly by state. In Minnesota, for example, the average is $29 hourly. In North Carolina, it’s $20. See the Genworth Cost of Care Survey to estimate these costs in your state.

2. At-home healthcare

What is at-home healthcare?

At-home healthcare is provided by a trained home health aide, working under the supervision of a doctor or nurse. The home health aide helps the senior with ADLs, but additionally is qualified to administer medications, check the senior’s vital signs, and generally monitor the senior’s physical and mental condition.

As with a home care aide, you and your service provider would design the in-home care plan under the guidance of the senior’s physician or nurse. The aide’s regular duties may include:

- Help with grooming, dressing, and toileting

- Companionship

- Housekeeping

- Meal preparation

- Transportation to medical and other appointments

- Assistance with the senior’s exercise regimen

- General monitoring of the senior’s physical and mental condition

- Temperature, pulse, blood pressure, and respiratory checks

- Administration of prescribed medications

- Handling of medical equipment

What does at-home healthcare cost?

The national average hourly rate for a home health aide is $23. Again, the going rate is dependent on where you live. Louisiana residents can hire a home health aide for $17 an hour, but you’ll pay more than $30 hourly in the state of Washington.

3. Adult day care

What is adult day care?

Adult day care is out-of-home, daytime supervision for seniors who aren’t independent enough to be left alone. Some facilities offer mainly social and custodial services, while others provide medical supervision and specialized services for seniors with memory loss. Care plans are designed with the senior’s needs in mind but are limited by the facility’s capabilities. Services may include:

- Help with grooming and toileting

- Social interaction with peers

- Meal preparation

- Educational classes and learning opportunities

- Physical and cognitive therapy sessions

- General monitoring of the senior’s physical and mental condition

- Temperature, pulse, blood pressure, and respiratory checks

- Administration of prescribed medications

- Handling of medical equipment

What does adult day care cost?

Adult day care facilities usually charge a daily rate, which averages $75 nationwide. That translates to $1,625 monthly or just under $20,000 annually. Your costs may be more or less, depending on where you live and the services your senior requires. There may be up-charges associated with specific conditions, such as dementia, for example. Even so, adult day care is an affordable alternative to a home health aide, which costs more than $200 on average for a nine-hour day.

4. Adult assisted living

What is assisted living?

Assisted living is housing designed for seniors who need custodial and medical care. Some of these communities are geared specifically for seniors with dementia or memory loss; these are known as memory care facilities.

Assisted living communities are designed to offer residents some level of independence, while providing them with the supervision and daily structure they need. Services can include:

- Help with grooming and dressing

- Social interaction with peers

- Housekeeping

- Meal preparation

- Transportation to medical and other appointments

- Assistance with the senior’s exercise regimen

- General monitoring of the senior’s physical and mental condition

- Temperature, pulse, blood pressure, and respiratory checks

- Administration of prescribed medications

- Handling of medical equipment

- 24-hour emergency care

Some seniors may stay in an assisted living community temporarily while recovering from an injury or medical procedure. Most residents, however, remain in the assisted living community long-term, or until they need clinical care provided in a nursing home.

What does assisted living cost?

Nationwide, assisted living programs cost about $4,000 monthly, or $48,000 per year.

5. Nursing home care

What are nursing homes?

Nursing homes provide medically supervised, residential care for seniors. They’re also known as skilled nursing facilities, long-term care facilities, convalescent care, or rest homes. The services are similar to those offered in an assisted living community:

- Help with meals, grooming, and dressing

- Social interaction with peers

- Housekeeping duties and preparation of meals

- Transportation to medical and other appointments

- Assistance with the senior’s exercise regimen

- General monitoring of the senior’s physical and mental condition

- Temperature, pulse, blood pressure, and respiratory checks

- Administration of prescribed medications

- Handling of medical equipment

- 24-hour emergency care

The primary difference between a nursing home and an assisted living community is the environment. A nursing home is a clinical space, more like a hospital. Assisted living has a residential feel, more like an apartment complex with shared community spaces.

How much does skilled nursing home care cost?

Outside of a hospital, nursing homes deliver the highest level of care available for seniors and disabled individuals. As such, it’s the most expensive form of senior care. On average, a month’s stay in a nursing home costs between $8,200 and $9,500. The lower end of the range represents the average cost for a semi-private room, while the upper end is the average cost of a private room.

According to the CDC’s National Nursing Home Survey, last conducted in 2004, the average length of stay for long-term nursing home residents is 835 days. At an average monthly cost of $9,000, a two-and-a-half-year stint in a nursing home would amount to $270,000 in long-term care costs.

Start planning for senior care costs now

It’s never too early to plan for senior care costs, for yourself or your loved ones. Normally, these planning efforts are a subset of your broader estate and financial plan, developed under the guidance of a trustworthy financial advisor or elder care attorney. Your advisor might recommend, for example, some combination of long-term care insurance, life insurance, long-term savings contributions, or the initiation of a Medicaid spend-down — a strategy to achieve Medicaid eligibility.

Unfortunately, none of these strategies can be completed overnight. That means the best time to plan for senior care costs is right now, even if you’re not yet sure what services you or your loved one might need.